The Cultural Practices of Literacy Study

CPLS Database

The CPLS database is a collection of ethnographic case studies of literacy practice in various marginalized cultural communities. The database is intended to both document various literacy practices and facilitate cross-case analyses of these practices. We believe that principled cross-case analyses facilitated by this database will allow us to (a) reach for greater generalizability than that afforded by a single case, and (b) deepen understanding and explanation of literacy and the ways that it manifests itself and mediates the lives of people across different cultural contexts.

Development of the Database

This database has undergone several iterations. It began as a simple Excel spreadsheet, yet through this first attempt at a meta-matrix (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Purcell-Gates, 2007), we realized that we could not do much more than 'count instances' across contexts without bringing to bear deep knowledge of each case within which the instances were actualized and imbued with meaning. We then decided to include in our definition of database the qualitative data that informed each case study as well as the researcher interpretations of that data. As a multi-dimensional database, this can be used by researchers with the 'flat database' (LeCompte & Schensul, 1999, p. 127) of theoretically coded literacy events.

Characteristics of the Database

As of July 2013, the CPLS dataset includes qualitative and quantitative -- interpretive and descriptive -- data, corresponding to 24 ethnographic case studies that have been carried out in different countries. However, the number of case studies included in the dataset is expected to continuously increase, thus adding new data to an expanding and evolving database. The data that composes our dataset then reflect the many different facets of literacy as it is practiced around the world. All data have been provided by the original authors of the case studies. The dataset can be accessed by any CPLS-affiliated researcher for future cross-case analyses. Affiliated researchers retain sole authorship rights of their individual studies and are guaranteed acknowledgement (reference) in any future analyses by other CPLS researchers who use data from their studies. The CPLS Literacy Practice Database consists of two types of data: (a) The multi-dimensional case study data; and (b) the theoretically coded literacy events contained in a flat dataset. The case study data is stored within Hermeneutic Units (Atlas.ti format). For each study, researchers load into an Atlas.ti Hermeneutic Unit their field notes, interview transcripts, interview protocols, photos of environmental texts found in the communities under study (e.g., signs, books, advertisements, magazines, etc.), scanned artifacts collected during the conduct of the field work (e.g., newspapers, flyers, memos), official documents, and all other collected data such as the demographic information of participants, video recordings, etc. Below are examples of these types of data:

Coded Photographs of Environmental Texts

Atlas.ti allows for coding of various images.

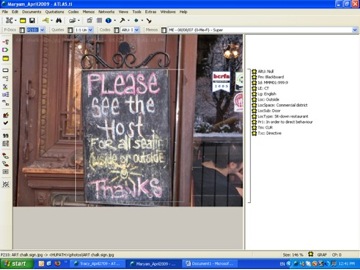

This screen shot shows the code string for an environmental text (a blackboard with a directive to potential customers) observed by a researcher in Vancouver, Canada. The string of codes provides information such as which case study the text came from, the location/context for this text, the purpose for the text, and so forth. A second example of a coded image:

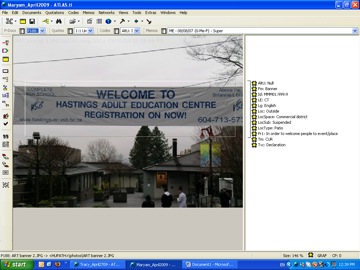

The code string for this environmental text (a banner with a welcome message for potential students) observed by a researcher in Vancouver, Canada. The string of codes provides information such as which case study the text came from, the location/context for this text, the purpose for the text, and so forth.

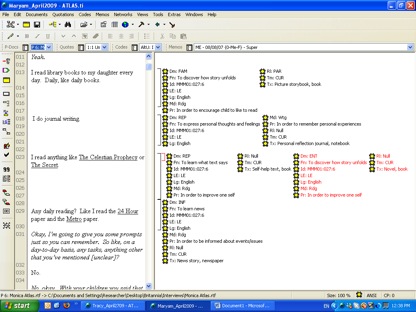

The screenshot below provides an example of how CPLS researchers transcribe and code interviews.

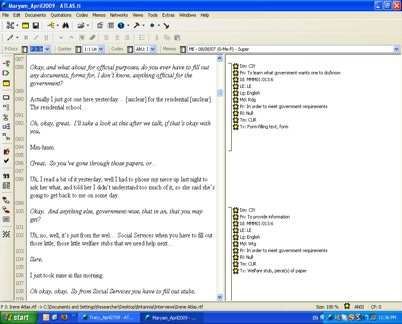

In this example, the researcher has identified and coded various literacy events described by the participant. The code string identifies information such as the social activity domain of the participant within which the event happened, the text that was read/written, the social purpose for the reading/writing of that text, and the online reading function for reading/ writing that text. A second example of a coded interview transcript, in which the researcher has identified and coded various literacy events described by the participant:

The code string identifies information such as the social activity domain of the participant within which the event happened, the text that was read/written, the social purpose for the reading/writing of that text, and the online reading function for reading/writing that text. We also upload final reports and other working papers as well as conference presentations - all accounts of researcher interpretation of the data. The data are then coded iteratively according to (a) researcher interest/questions; and (b) common literacy event codes and conventions used across the CPLS cases.

Data exported from Atlas.ti into Excel spreadsheets

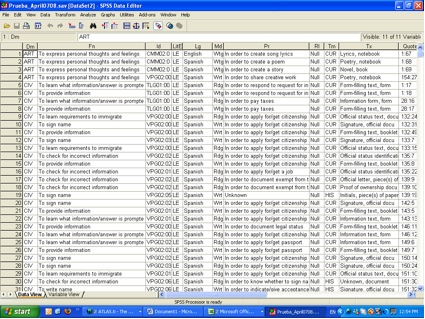

The flat database begins in Atlas.ti where the coding is done and then exported to a meta-matrix in text format. This database contains both (a) codes that serve data management and descriptive purposes, and (b) theoretically-based codes for conceptual purposes. Within the main part of the database, we have used a code string with nine code types for each identified literacy event. Among these nine codes, four are conceptually-based and related to our emerging model of a literacy practice while the others are considered more descriptive. (For information on demographic codes, please see Analyzing Literacy Practice: Grounded Theory to Model in the Working Papers section.) The CPLS team developed a way to import data coded within Atlas.ti into an Excel spreadsheet, which serves as a "flat" database:

Although this screenshot only shows a small fraction of this flat database, it shows that each specific code from the code strings in Atlas.ti is imported into the database, allowing for comparisons to be made across cases. In addition to coded data from Atlas.ti, the "flat" database also includes demographic data about participants from each case study.

Currently, the database includes data from participants with 16 different nationalities, 20 native languages, 56 occupation types, all levels of schooling, 4,555 individual literacy events, 349 different functions of reading/writing, 342 social purposes of reading/writing; texts written in 23 different languages, and 774 different types of texts read or written. These numbers are constantly rising as new data from completed projects are entered.

Cases in the Database

Researcher |

Context |

Description of Case |

| Annah Molosiwa | Botswana | A case study of four Botswanan graduate students, studying in the US, explores current language and literacy issues in Botswana. |

| Angeles Clemente | Oaxaca, Mexico | The ecology of reading and writing within the context of a prison and the everyday lives of its inmates |

| Angeles Clemente | Oaxaca, Mexico | The literacy practices of a group of elementary school students learning English, who for the most part come from a shelter |

| Angeles Clemente | Oaxaca, Mexico | Literacy practices of future English teachers currently enrolled in the teacher education program at a public university |

| Cathy Mazak | Puerto Rico | Two farmers' usage and attitude towards English. |

| Cathy Mazak | Puerto Rico | This ethnographic case study explores the usages of English in a rural, Puerto Rican community |

| CPLS | Vancouver, Canada | The literacy practices of several families living in a marginalized, mainly non-English L1 urban neighborhood |

| Chad O'Neil | Michigan, USA | This case study looks at the influence of home and school on the literacy practices of two mid-Western, American undergraduate students. |

| Doug Eyman | North Carolina, USA | The author examines how curricular and pedagogical work of a course in writing and technology appears to help students acquire a technology discourse and reflect critically upon their digital literacy practices |

| David Gallagher | Michigan, USA | Texts and social literacy purposes are compared between in and out of school contexts for a group of struggling adolescents in an urban American school. |

| Gaoming Zhang | Michigan, USA | A case study of two Chinese American bilingual families examines literacy activities, beliefs, and values |

| Ji-Eun Kim | Vancouver, Canada | This case study explores the changes of one family's literacy practices brought about by life changes after immigrating from Korea to Canada |

| Juliet Tembe | Uganda | The relationship between home literacy practices of a rural, Ugandan family examines the relationship and the Ugandan government's new language (English) education policy |

| Jodene Kersten | Michigan, USA | This case study compares the home and school literacy practices of a group of fifth grade, urban students attending an after-school program in the US |

| Kristen Perry | Michigan, USA | A case study of the literacy practices of three male Sudanese refugee youth living in Michigan, US. |

| Kristen Perry | Michigan, USA | The literacy practices of three Sudanese families with young children, focusing on the families' reliance on literacy brokering, or informal assistance to understand some of the texts they encountered. |

| Kalinka Zarate | Oaxaca, Mexico | Relationship between the cultural practices of literacy and the variability in the written L2 Spanish by elementary children who are speakers of L1 Zapotec |

| Kamila Rosolova | Michigan, USA | This case study examines the literacy practices of two adult Cuban refugees in the US |

| Mario Gopar | Oaxaca, Mexico | The cultural literacy practices and hopes for their children of parents with no or low school, who have moved from rural to urban areas |

| Maryam Moayeri | Vancouver, Canada | The literacy practices in an East Vancouver neighborhood whose elementary school ranks in the lowest quartile of British Columbia schools. |

| Stephanie Collins | Indiana, USA | This case study describes one teenaged, female African-American's in- and out-of-school literacy practices, and the transactions she makes between them |

| Tracy Gates | Bolivia | The alignment between the culture and literacy practices of students and the Bolivian Fe y Alegria School, as well as the ways in which teachers are prepared to teach in ways that value and incorporate the community's practices. |

| Victoria Purcell-Gates | Michigan, USA | The literacy practices of L1 Spanish migrant farm worker families and their children's literacy experiences attending English Head Start programs. |

| Victoria Purcell-Gates | Costa Rica | The relationship between the in- and out-of-school literacy practices of marginalized Nicaraguan immigrant students |

References

- LeCompte, M.D. & Schensul, J.J. (1999). Designing & Conducting Ethnographic Research. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.ReferencesReferences

- Miles, M.B., & Huberman, A.M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Purcell-Gates, V. (Ed.). (2007). Cultural practices of literacy: Case studies of language, literacy, social practice, and power. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.