Power vs. the People: How Maine Voters Saved Ranked-Choice Voting

By Seth Woods

The voters of Maine have spoken about how they wanted their elections to be conducted. Several times. Yet their legislators have repeatedly tried to prevent the electorate’s wishes from being fulfilled.

Since 2001, election reformers have lobbied the Maine Legislature to change the way government officials were elected in the state, by replacing the traditional plurality voting system (also known as “winner-take-all” or “first past the post”) with a preferential voting system that requires a candidate to receive support from a majority of voters. In Maine, the proposed new system was called “ranked-choice voting,” (RCV) while in other cities around the country it’s known as “instant runoff voting.” 13 cities (including Maine’s largest city, Portland) currently use RCV for local elections – though this number will increase, as voters in Memphis rejected the city council’s last-ditch effort to repeal the program before next year’s municipal elections. Maine is the first state to conduct federal elections using RCV.

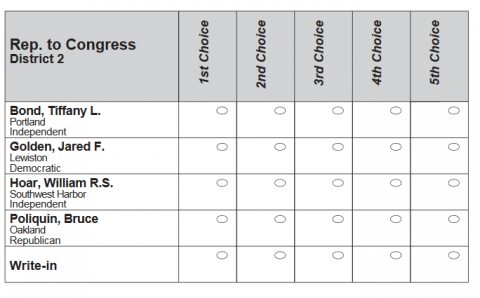

Instead of only voting for one candidate in a race, ranked-choice voting allows voters to sort candidates based upon the voter’s personal preference. Candidates with the fewest first-choice votes are eliminated, and the ballots cast for eliminated candidates are reallocated to the voter’s next-best choice. The process repeats until someone is elected with a majority (50% + 1) of the votes.

For example, if a voter wanted to vote for a minor party candidate, the voter could mark the minor party candidate as their first choice and a major party candidate as their second choice (were their first-choice candidate to be eliminated). RCV limits the “spoiler effect” minor parties are occasionally accused of after close elections, and counters the claim that voting for independents and minor-party candidate is like “throwing your vote away.” RCV has also been shown to reduce negative campaigning: candidates are less likely to attack opponents when those opponents’ supporters could swing the race with second-choice votes.

This idea of ensuring every voter’s voice is heard is especially relevant in Maine, where voters are notorious for supporting independent candidates. One of their U.S. senators is a declared independent, and was re-elected with 55% of the vote. The outgoing governor was elected and re-elected in contentious three-way races, both times failing to get more than 50% of the vote. Six members of the state House were elected as independents in the 2016 election.

Ultimately, it was the voters that decided it was time to bring ranked-choice voting to the state. After more than a decade of failed attempts to pass RCV through the legislature, reformers gathered enough signatures to bring the proposal directly to the voters, which passed with 52% of the vote in November 2016. However, leadership in Augusta still had their concerns about the program’s implementation, claiming that the system would be confusing to voters and burdensome on local election clerks. Upon request of the state senate, the Maine Supreme Court issued a unanimous advisory opinion that RCV was unconstitutional in respect to general elections for state legislators and governor.

With the Court’s ruling in their pocket, the state legislature passed a law delaying the implementation of RCV indefinitely unless the law was passed as a constitutional amendment – a process that requires 2/3 support from both chambers of the legislature before it can go before the electorate. Multiple lawsuits were filed in favor and opposition to the bill, culminating in a state Supreme Court mandate that RCV be used to conduct the 2018 primary election. The governor announced he would not certify any results of RCV elections, calling ranked-choice voting “the most horrific thing in the world.”

Considering RCV had stalled in the capitol for so many years, activists had to mobilize quickly if they were going to defend the new system from legislators hoping to bury it. By March, proponents of the program had acquired enough signatures to put the legislature’s bill up for a “people’s veto” that would override the legislature’s delaying tactics. The veto vote was held during the June 2018 primary election (which also served as the first statewide election to use ranked-choice voting in Maine), and the electorate once again sided with RCV and against the legislature. Having overridden all legislative maneuvers, ranked-choice voting had finally become the law of the land.

Last Tuesday’s election was the first time ranked-choice voting was used in a general election in Maine. Only three races used the ranked-choice system (U.S. Senator and the two U.S. Representatives) and in two of those races, a candidate reached the 50% threshold on the first count with no need to eliminate candidates or re-allocate votes. The third race (in the 2nd Congressional District) will be decided by the ranked-choice system later this week. Republican Bruce Poliquin and Democrat Jared Golden each garnered 46% of the vote; how the remaining 8% of the votes split between the two candidates will decide which one will head to DC in January. The winner is expected to be announced tomorrow.

Pictured: A sample ballot in Maine’s 2nd Congressional District using ranked-choice voting. From the Maine Secretary of State’s website: https://www.maine.gov/sos/cec/elec/upcoming/pdf/CD2.SampleBallot.pdf