How to Make the National Popular Vote Winner the President

By: Roger Morris

To some people the Electoral College is an overly complex system that inhibits the will of the American people. A compelling argument in favor of this notion is the fact that a candidate can be elected President without receiving the most votes. This scenario has happened four times in American history: 1824, 1876, 1888, and 2000. Because of this, there has been a movement to shift the United States to a national popular vote system where the candidate with the most votes nationally wins the election.

Opponents of the Electoral College have laid out several reasons why the system is inadequate. Presidential elections could be considered competitions to win swing states and not the nation as a whole. Even amongst those swing states there is a strong incentive to focus on the states representing a larger worth in the Electoral College. During the 2012 campaign, about two-thirds of general-election campaign events (176 of 253) were in four swing states: Ohio, Florida, Virginia, and Iowa. This year, 91% of campaign events (319 of 351) since the nominating conventions have been in only 11 states, with nearly 60% of those events occurring in Ohio, Florida, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania. In 25 states, there have been a combined total of zero presidential campaign events during the general-election cycle. Opponents argue that this focus on only a few states comes at the expense of the rest of the country. Candidates have every reason to focus on issues and tailor their promises to please citizens of swing states.

In addition, citizens in states that are not competitive and receive no visits from candidates may see little reason to vote. If a voter wants to vote for a Democrat but lives in a state that always casts its electoral votes for Republicans, they may choose not to vote because they feel their vote has an incredibly small chance of making a difference. A national popular vote system could provide an incentive to these disenfranchised voters and allow their votes to hold more worth.

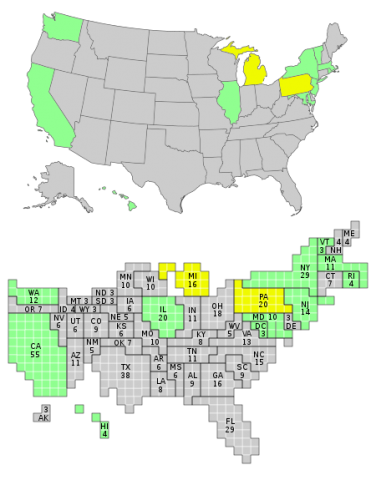

The Electoral College system is laid out in Article II and the Twelfth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Therefore, abolishing the Electoral College would require a Constitutional Amendment. Past efforts to make this change have been unsuccessful due to Amendments being notoriously difficult to pass. They require a two-thirds vote in each chamber of Congress and, if successful in Congress, ratification in three-fourths of state legislatures. However, a plan to sidestep the Amendment process called the “National Popular Vote Interstate Compact” has gained some traction. It currently has the support of the District of Columbia and ten states.

The plan was first proposed following the 2000 presidential election by Northwestern law professor Robert Bennett and expanded upon by law professors Akhil Amar of Yale and Vikram Amar of the University of Illinois. The legislatures in the ten states and DC have decided that they will have their electors cast their state’s electoral votes for whichever candidate wins the national popular vote. If every state were to pass this legislation we would maintain the Electoral College, but avoid situations like the 2000 presidential election where the candidate that won the national popular vote lost the Electoral College vote and did not become President. In 2000, the election came down to one state, Florida, which Al Gore lost by a few hundred votes. With the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact in place Gore would have won the presidential election by virtue of winning the national popular vote regardless of the total in Florida. If every state were to adopt this measure the winner of the national popular vote would win all 538 electoral votes.

There is some question of whether the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact is constitutional. Under Article I of the Constitution, Congress must approve compacts between states. At the same time, Article II reserves to the states the exclusive power to bind their electors. Whether this legislation is an end run around the Constitution has yet to be taken up by the Supreme Court.

The Compact will not go into effect until enough states join the plan to collectively represent a majority of electoral votes, 270. At that point, the winner of the national popular vote would always win a majority of electoral votes. As of 2016, the movement has the support of states with a combined 165 electoral votes. There are two currently active bills in the statehouses of Pennsylvania and Michigan, which could bring the total electoral votes controlled by this measure to 201. If Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton were to win the presidency despite losing the popular vote, we may see a new push to put the compact in place.