In

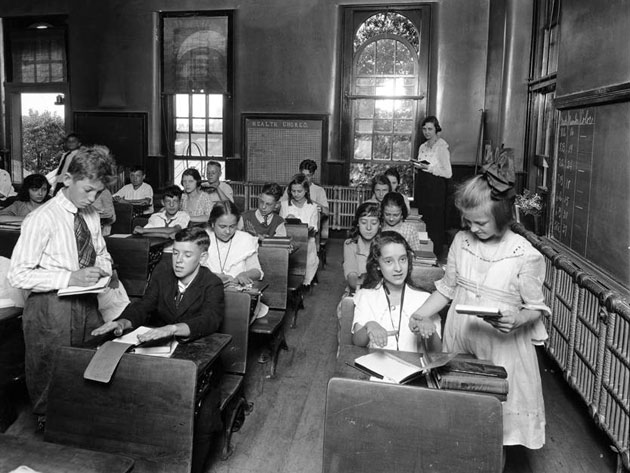

the 1890s the high school was a highly selective and still voluntary

institution. By the 1920s, it was, for better or worse, the "people's

college," at once unselective and compulsory. The repercussions

were enormous. They were felt in the curriculum, in prevailing understanding

of the life cycle -- of what it meant to be "an adolescent" --

and in the texture of your people's day-to-day experience. The new

high school helped to magnify the already apparent differences between

big city life, the small towns, and the countryside, and because

compulsory attendance laws went hand in glove with child labor restrictions,

it also contributed to the reorganization of the work place.

On the high school of the 19th century, see William J. Reese, The Origins of the American High School (Yale University Press, 1995).

On the redefinition of the life cycle see Joseph Kett, Rites of Passage: Adolescents in America, 1700 to the Present (Basic Books, 1977) and Steven Mintz, Huck's Raft: A History of American Childhood (Harvard, 2004). William A. Link makes explicit the connections between the high schools and public health in The Paradox of Southern Progressivism (University of North Carolina Press, 1992).

For broader but conflicting assessment of the high school's expansion -- especially for what would be known in '50's as "Education for Life Adjustment" -- Lawrence Cremin, The Transformation of the School: Progressivism in American Education 1876 to 1957 (Vintage Books, 1961) and Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (Vintage Books, 1962) still make a fine starting point.

On the high school of the 19th century, see William J. Reese, The Origins of the American High School (Yale University Press, 1995).

On the redefinition of the life cycle see Joseph Kett, Rites of Passage: Adolescents in America, 1700 to the Present (Basic Books, 1977) and Steven Mintz, Huck's Raft: A History of American Childhood (Harvard, 2004). William A. Link makes explicit the connections between the high schools and public health in The Paradox of Southern Progressivism (University of North Carolina Press, 1992).

For broader but conflicting assessment of the high school's expansion -- especially for what would be known in '50's as "Education for Life Adjustment" -- Lawrence Cremin, The Transformation of the School: Progressivism in American Education 1876 to 1957 (Vintage Books, 1961) and Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (Vintage Books, 1962) still make a fine starting point.